The Smart Retailer’s Guide to Competition-Based Pricing

The Smart Retailer’s Guide to Competition-Based Pricing

In the 2010s, flagship smartphones first crossed the $1,000 price point with Samsung’s Galaxy Note 8 and Apple’s iPhone X, but many consumers have noticed that the once high-water mark price has become standard as competition-based pricing has kept prices consistently high.

Today, Samsung and Apple’s flagship phones retail from $1,000 to $1,500, with $1,000 being a common price for a mobile device.

While some buyers see this as a trend in rising prices, from a longer perspective, $1,500 is an incredible deal. In 1973, Motorola began to prototype the world’s first commercial cell phone – the DynaTAC 8000X – and when it hit the market in 1984, it retailed for $3,995 (well over $10,000 in today’s dollars).

Why are phones so much cheaper today? Why do they seem to be getting more expensive? The simple answer is that the costs of development and manufacturing have changed over time, but that answer leaves out a significant part of the story: Competition is a big factor in how cell phone companies price their phones.

Competition-based pricing is a widespread retail pricing strategy, and while it’s only part of the equation, anybody concerned with profitability should understand and utilize it to an extent.

As companies scramble to optimize their profits, new AI tools are available for a new generation of business leaders, making competition-based pricing more accurate and effective than ever.

Key Takeaways:

- In competition-based pricing, competitor prices are a major influence on a retailer’s prices.

- Competitor prices may influence your strategy in several ways, including undercutting (loss leader) and quality signaling (perceived value).

- Competition-based pricing is one of many different pricing strategies that you can use in concert with each other.

- Today’s profit optimization is driven by AI-enabled technology from Hypersonix.

What is Competition-Based Pricing?

Competition-based pricing means exactly what it sounds like: pricing based on competition. Also called “competitive pricing” or “competitor-based pricing,” competition-based pricing is a pricing strategy wherein a retailer uses the prices of their competitors as a heavy influence on their own prices.

How to Use Competition-Based Pricing

In practice, of course, competition-based pricing is more complicated than simply matching your competitors. How exactly should your competitor’s prices influence your own?

Undercut the Competition

Retailers may use competition-based pricing to undercut their competition and secure a larger share of the market, improve brand loyalty, and sell related products. You can see this strategy at play in Charles Schwab’s race to no-commission stock trades.

Before the 1970s, every brokerage firm charged the same commission for identical trades. When that changed in 1975, it set off a race to the bottom. Since Charles Schwab was a giant among brokerage firms, it lowered its commissions, knowing that its competitors would have to either lose customers or lose profit, and this strategy paid off.

In the world of retail, Walmart has used such extensive undercutting tactics that a phrase has emerged to describe the impact they have on its competitors: “The Walmart Effect.” Walmart notoriously undercuts its competitors to secure a larger share of the market. While competition is only one component of its Everyday Low Pricing (EDLP) strategy, it’s an important component.

Quality Signaling

As the counterpoint to undercutting is quality signaling. As a larger trend of psychological pricing, quality signaling capitalizes on consumers’ instincts that a cheap product must be low quality, while a more expensive product must be luxury.

In his book Free: The Future of a Radical Price, author Chris Anderson explains that it’s actually easier to sell a product for one cent than to give it away for free. People don’t want free things because their instinct tells them that a free product must be worthless, but the more they pay for it, the more they see the value in it.

A prominent example of this quality signaling strategy is Starbucks. Quality is a huge part of Starbucks’s brand identity, and its pricing strategy is heavily centered around outpricing its competitors as a way of signaling quality. Quality signaling is most closely related to value-based pricing, but to be effective, Starbucks tailors its prices based on its competitors in each market.

Similarly, retail stores like Target and Whole Foods offer higher prices in part because of the quality that a higher price tag can signal in the mind of a consumer.

The Alternatives to Competition-Based Pricing

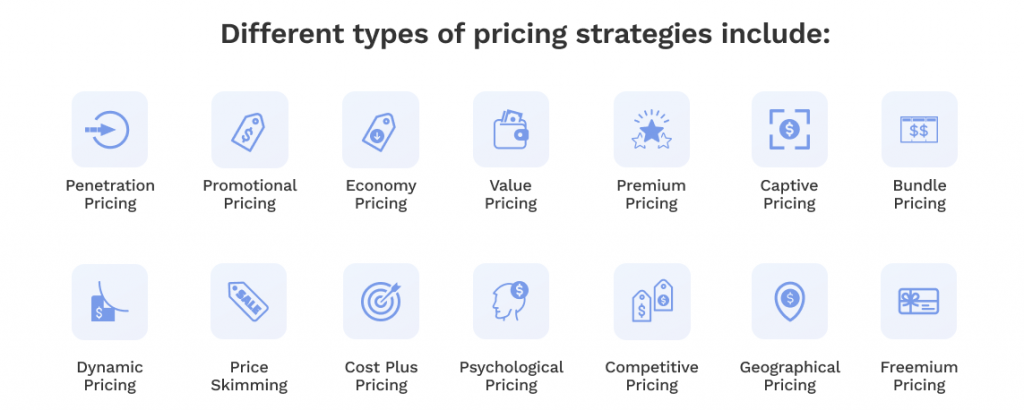

As the examples of retail giants Walmart and Whole Foods illustrate, competition-based pricing doesn’t exist in a vacuum: Most retailers use it along with other strategies like price skimming or EDLP. Competition-based pricing isn’t an island, but rather a category of pricing strategies, and along with cost-based and demand-based pricing, competition-based pricing is one of the major pricing strategies retailers use.

Cost-Based Pricing

Also known as “cost-plus pricing,” cost-based pricing is the strategy of setting prices based on the cost to manufacture or acquire a product. Typically, retailers mark up products about 2x their wholesale value, but the exact amount depends on the other pricing strategies the retailer is using.

Cost-plus pricing is common in retail settings like clothing or department stores that compete on selection and brand rather than primarily on price. Cost-based pricing is popular because it’s relatively simple to calculate and fair across the board, but it also has disadvantages. The simplicity of cost-based pricing is its biggest advantage and disadvantage because while it can keep prices consistent and fair, that means retailers could miss out on opportunities to raise prices in times of higher demand.

Demand-Based Pricing

Also known as “value-based pricing,” demand-based pricing doesn’t primarily consider competitors or costs, but rather what a customer is willing to pay.

This strategy is most prevalent within luxury retail brands where the perceived value of the product is substantially higher than the material value of manufacturing and selling it. Demand-based pricing is good for companies with strong perceived value and established brand recognition. It’s also good for customers because they’re paying the value that the average customer is happy with.

However, this strategy leaves retailers vulnerable to undercutting, especially in industries where brand recognition is less important than quality.

Competition-based, cost-based, and demand-based pricing are the three pillars of pricing strategy, but they’re only a handful of the strategies available to retailers. These ideas are not mutually exclusive – as you saw with the example of Starbucks, competition-based and demand-based pricing go hand-in-hand to inform Starbucks’s pricing strategies.

How Technology is Enabling Profit Optimization

A good pricing strategy is highly effective but complicated to formulate and implement.

That’s where Hypersonix enters the picture.

Hypersonix builds on time-tested profitability strategies like dynamic pricing and competitive pricing. It uses the power of AI and machine learning to uncover better-than-ever strategies to maximize your profit.

While competition-based pricing is a valuable strategy for retailers, Hypersonix can revolutionize the way you approach profit optimization, helping you build better strategies, make more informed decisions, and spend less time worrying about inventory and pricing.

To see how Hypersonix can help you maximize your profit, request a free demo today.

.png)